One fun fact about the data debate is that we don’t have data on data. We know that troves of data are being generated in cities from phones, sensors, ATMs, cameras, credit cards, interactions with public services… you name it. Well, you may name it, but you cannot count it. We know is a lot, but we don’t know how much.

In fact, it’s so much, that is probably too much. Specially if we don’t know what to use it for.

In my previous post I explored the specific indicators and data points that cities can use to manage the public space. The type of post that is informative for urban data geeks, but probably too weedsy for public leaders not directly involved in overseeing sidewalks. Definitely too specific for mayors.

And yet, mayors also need more clarity on what they can use data for. That is exactly the type of guidance that we felt is missing - we heard it from mayors themselves - so we (my colleagues Jorrit de Jong, Quinton Mayne and I) wrote an academic article about it: The Data-Informed City, recently published in the Information Polity Journal.

The data behind the data

Writing this academic article definitely took more time than putting together this post. To make sure it was grounded in existing research, we reviewed over one hundred academic articles on data in the public sector.

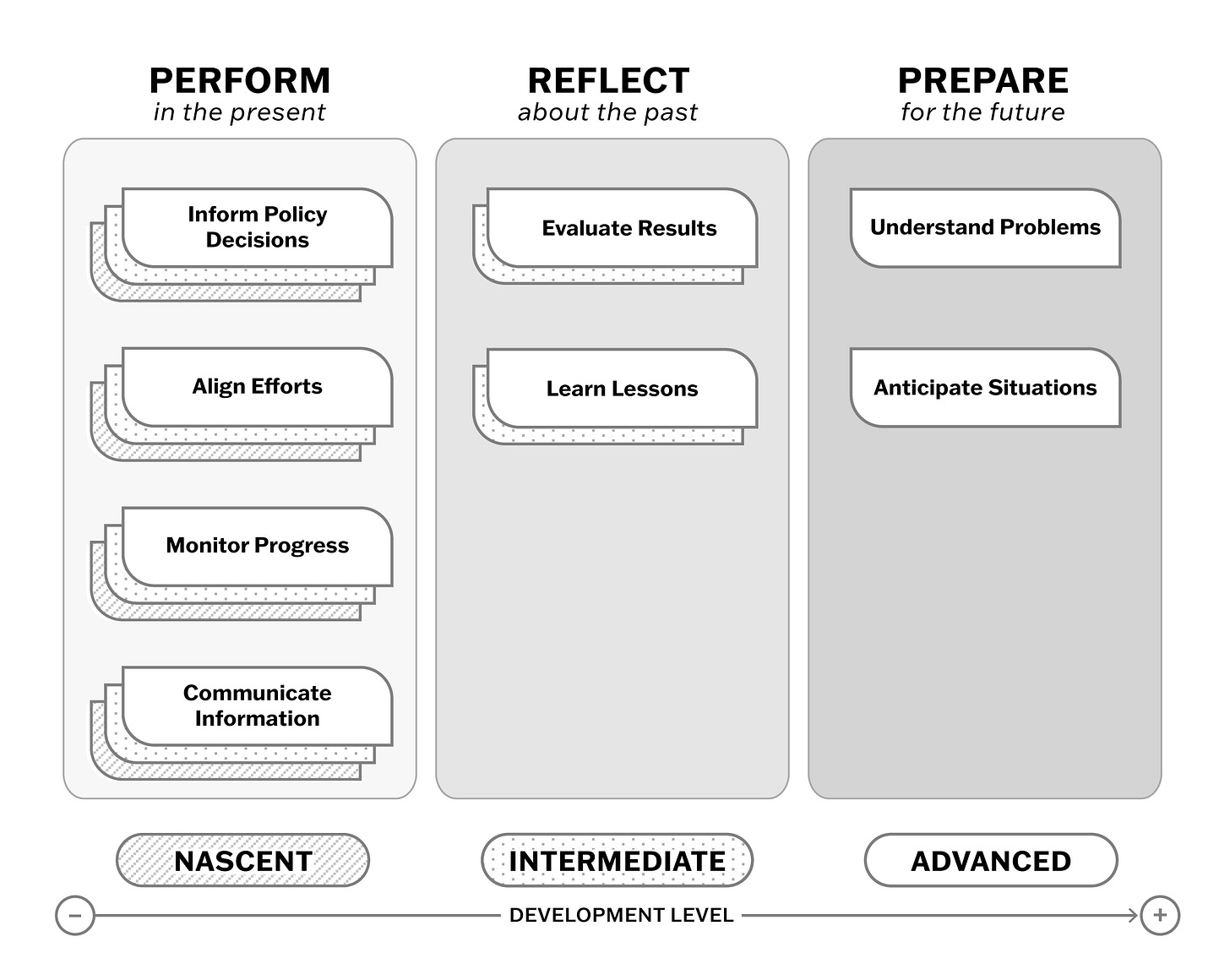

This, in addition to our own original research and our interactions with city officials, helped us identify eight main uses of data:

Understand problems: Use data to describe an issue or distinguish the components of a problem (e.g., to map individual journeys of homeless veterans accessing available services; to identify factors that affect illegal housing).

Inform policy decisions: Use data to guide the design and execution of programs or policies (e.g., employ satellite imagery and police data to allocate resources in code enforcement).

Communicate information: Use data to inform the public and engage with the community and stakeholders (e.g., use information derived from parking permit processes to communicate the status of resident requests through a 311 line; employ data-informed meetings with residents to share information about progress towards building affordable housing units).

Align efforts: Use data to bring stakeholders together around a problem and agree on a course of action (e.g., use data on individual properties obtained from different departments, such as fire, code enforcement, and police, to guide a task force charged with dealing with distressed properties).

Monitor progress: Use data to oversee operational performance and detect anomalies (e.g., employ agency data to measure service levels against expected targets and identify disparities).

Evaluate results: Use data to assess whether a program is producing desired results (e.g., run a quasi-experimental evaluation to determine whether a program reduced crime and improved residents’ wellbeing).

Learn lessons: Use data from different sources as a basis for reflecting on a city’s mission and operations, consider changes based on that reflection, and tease out learnings (e.g., employ a systems approach to tackle childhood obesity, evaluate the program, and apply the approach to other complex issues).

Anticipate situations: Use data to explore and devise organizational responses to potential future scenarios (e.g., use administrative data from past inspections to predict at-risk properties and prioritize future inspections).

Different data uses demand different maturity

These eight uses are not made equal. Using data to prove that a subsidy program increased access to housing and bettered the health of the city’s migrant community (through an RCT) is much more challenging than monitoring whether the subsidies were spent or not. Granted, sometimes even this is difficult given outdated systems and poor data quality. But then imagine establishing a random counterfactual group and measuring outcomes over time.

In the paper we flesh out what the different levels of maturity mean for each of the eight uses. We also clustered the eight uses according to whether they mainly help cities perform in the present, reflect about past performance, or prepare for future actions - and we tried to cram everything in a shinny visual:

If we are successful, this framework will serve as a compass for city leaders seeking to use data more intentionally. It can also help them identify areas where they need to invest to strengthen their city’s ability to use data for more complex applications.

The Data-Informed City is not just data-driven

I could have started with this point, but is also good as a closing remark.

There is a reason why we call it the data-informed and not the data-driven city: while data can be helpful in informing choices, it is not the only factor that matters. Awareness of the context in which data are collected and used, and incorporating other considerations - values and trade-offs - in the decision-making process are as important.

Data has also limitations, and biases, and therefore data shouldn’t be in the driving seat. That place is reserved for democratically elected city leaders, who can take data as an advisor, but not as their master.

If you find this framework useful, for research or for practice, do reach out. We would love to keep the conversation going!