Mapping the Invisible City

Collaborating to unearth data can help cities build faster, safer, and cheaper

“I highly recommend anybody to go look at your local city’s GIS and just turn on those layers and get a sense of the scale of what’s being built and what is being maintained under the city […] We’re talking about thousands and thousands of kilometers of pipes, valves, pipe bridges” Adam Jarvis chatting with Patrick Mckenzie at Complex Systems

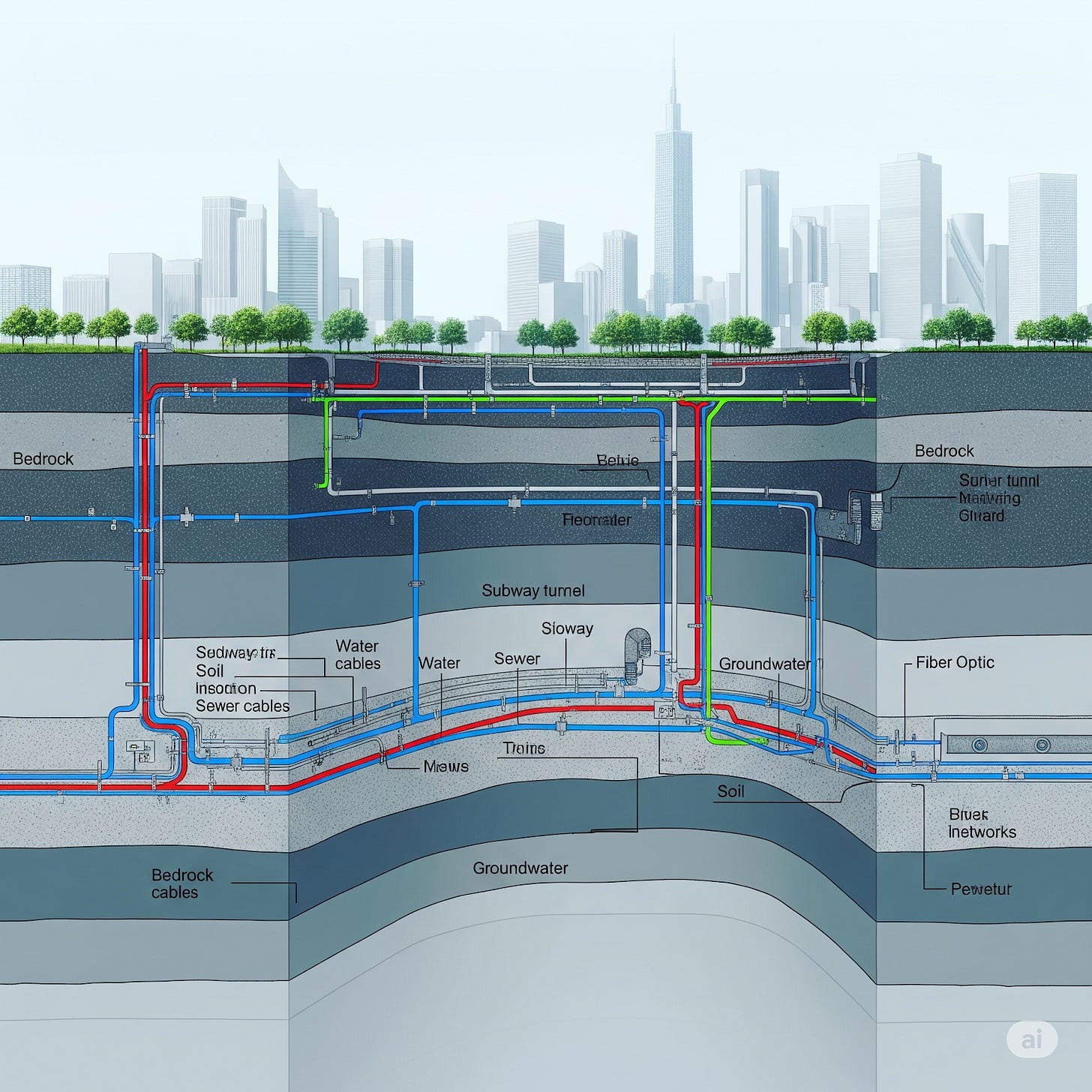

For all the talk about digital twins, we’re missing half of the “twin”: what happens underneath the earth. We all forget about the complex infrastructure that we have built so we can have potable water on demand, illuminate our rooms when outside is dark, or be connected to wifi - so I can publish this article…and you can read it.

Most cities don’t have accurate registries of the urban infrastructure underneath. Not even in New Zealand, one of the landmarks of sound public management. This 2023 excerpt is from a Wellington City Council press release:

Currently, there is no central record system for the infrastructure underneath Wellington’s – or New Zealand’s – streets. Data is held in the separate utilities companies’ databases, all of which keep data in different formats to meet their individual needs. With data compiled manually for each job it is very difficult to have a thorough understanding of the assets beneath the streets. Records from older pipes and cables are often missing or incomplete.

After all, it’s not that easy to simply turn on a city’s GIS of underneath layers.

But that’s changing in Wellington with the recently launched UAR (Underground Asset Register): a single trusted repository aggregating data from those owning assets beneath the surface.

Wellington’s experience building the UAR provides insights into why it’s so hard to build one and why it’s worth it nonetheless.

A Layered Patchwork of Pipes and Cables

The issue with a network image, such as the one below, is that it may give a false impression: one of a unified and well-planned web. In reality, few urban underground infrastructures were planned coherently, with engineers drawing a consistent network of pipes before starting building. Most networks have grown organically, one street at a time, building the information system in a piecemeal fashion. The companies laying the pipes and cables registered them in their own systems - often on paper -, before covering them with asphalt. And that was that.

Only when others excavate the same street to lay their own stuff do they discover what lives underneath the concrete. This “going blind” approach to building infrastructure is not only inefficient. It’s one of the reasons why building in legacy cities is so expensive. When excavators dig blindly and damage the wrong pipe, this can result in disruptions and repairs, as well as dangerous hazards for construction workers. Builders may also need to redesign original plans based on what they discover when they open the earth.

According to the calculations made by Wellington city council, the annual additional costs for sector participants due to these issues are north of $50 million. It’s also the cause of thousands of days of delay as well as health and safety incidents. Responses to a Wellington survey indicated that infrastructure companies experience one or more issues with data (missing, inaccurate, hard to use) in around 70 percent of digs and 50 percent of digs are affected by asset strikes, near misses, unexpected assets found, or expected assets not found.

At a time when many are saying that “it’s time to build”, having accurate data from under-surface has become essential for Building to be cheaper, safer, and on time.

How to Draw a Map with so Many Hands

The benefits of accurate information never seemed so clear, and yet few cities have quality information of what lies beneath. One reason is that the information was never recorded, or it was not digitized and adequately stored.

Even when the information does exist, however, it is held in many hands, in diverse systems and with different formats. Public entities - often different ones - may have data on water systems and sewage pipes. Information on network cables are owned by telecommunication companies, and energy utilities may hold the data on the power lines and gas pipes.

This data can be sensitive, both for security reasons and companies’ business interests, so they are not eager to share it. As it often happens with issues covered here in Datapolis, the crux of the matter is not technical. It is a governance challenge: precisely what makes Wellington’s UAR such an interesting case to “dig deeper into”.

The Governance of Data Sharing

In 2020, Wellington’s city council decided to map 16 kilometers of the city’s streets using GPR and Lidar technologies. They were astounded by what they found. Just in that relatively shorter mileage they identified 100 anomalies - including a collapsed water main. This pilot and an additional study gave them the justification they needed to secure the resources - 4 million dollars from the central government - to launch the pilot for an underground asset map.1

Identifying a need and getting funding to tackle it is one thing. Coordinating across the infrastructure sector is another. Aware of the importance of collaboration for the project’s success, the city council established a technical reference group with representatives from the city, the water entity, electricity and gas distributors, telecommunication providers, contractors and other experts.

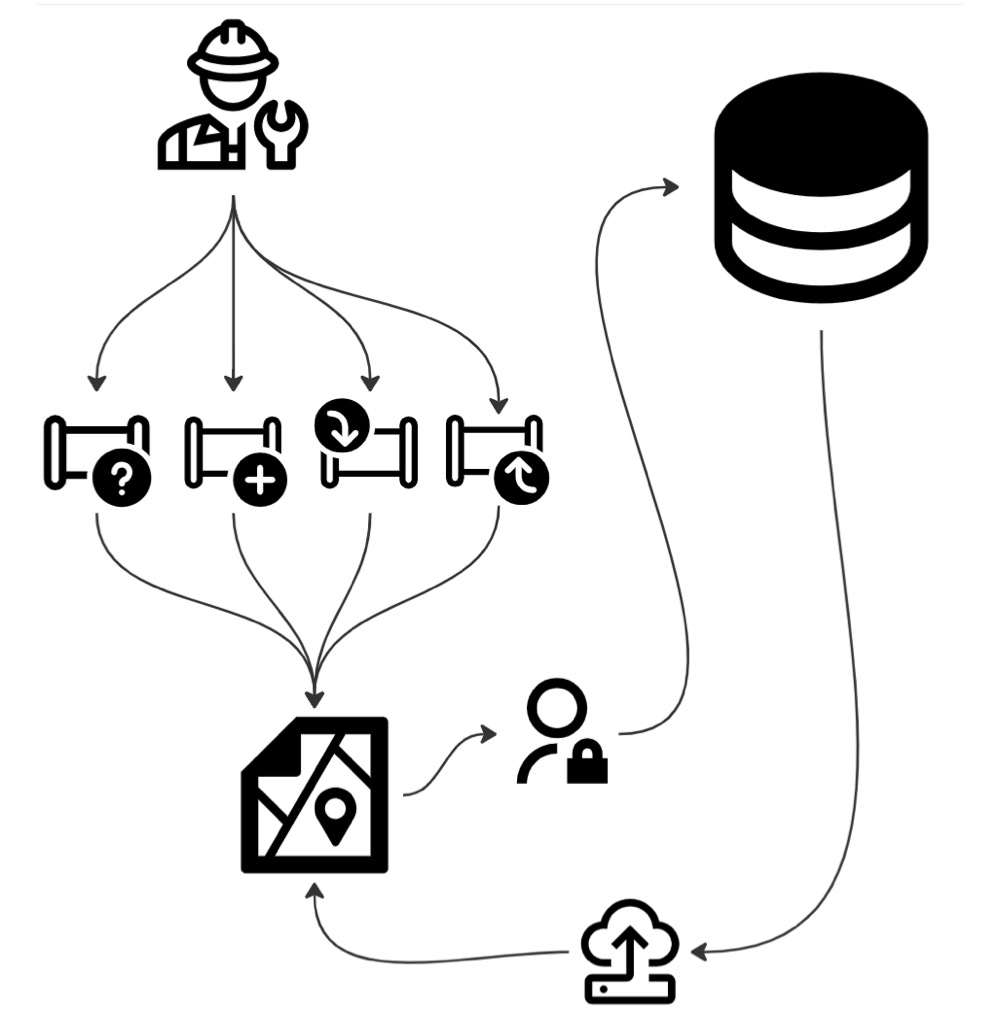

Another core piece of the governance framework was finding a neutral entity that would manage the register. This is key in any data sharing scheme. Companies and public entities sharing the data want to trust that whomever is receiving their data will not share it with anyone who shouldn’t have access to it. They also need to be confident of technical security aspects. In the case of the UAR, this intermediary role was played by Digital Built Aotearoa, a neutral not‑for‑profit entity that operates the platform and runs a federated data sharing scheme, ensuring that no one single entity controls all the data.

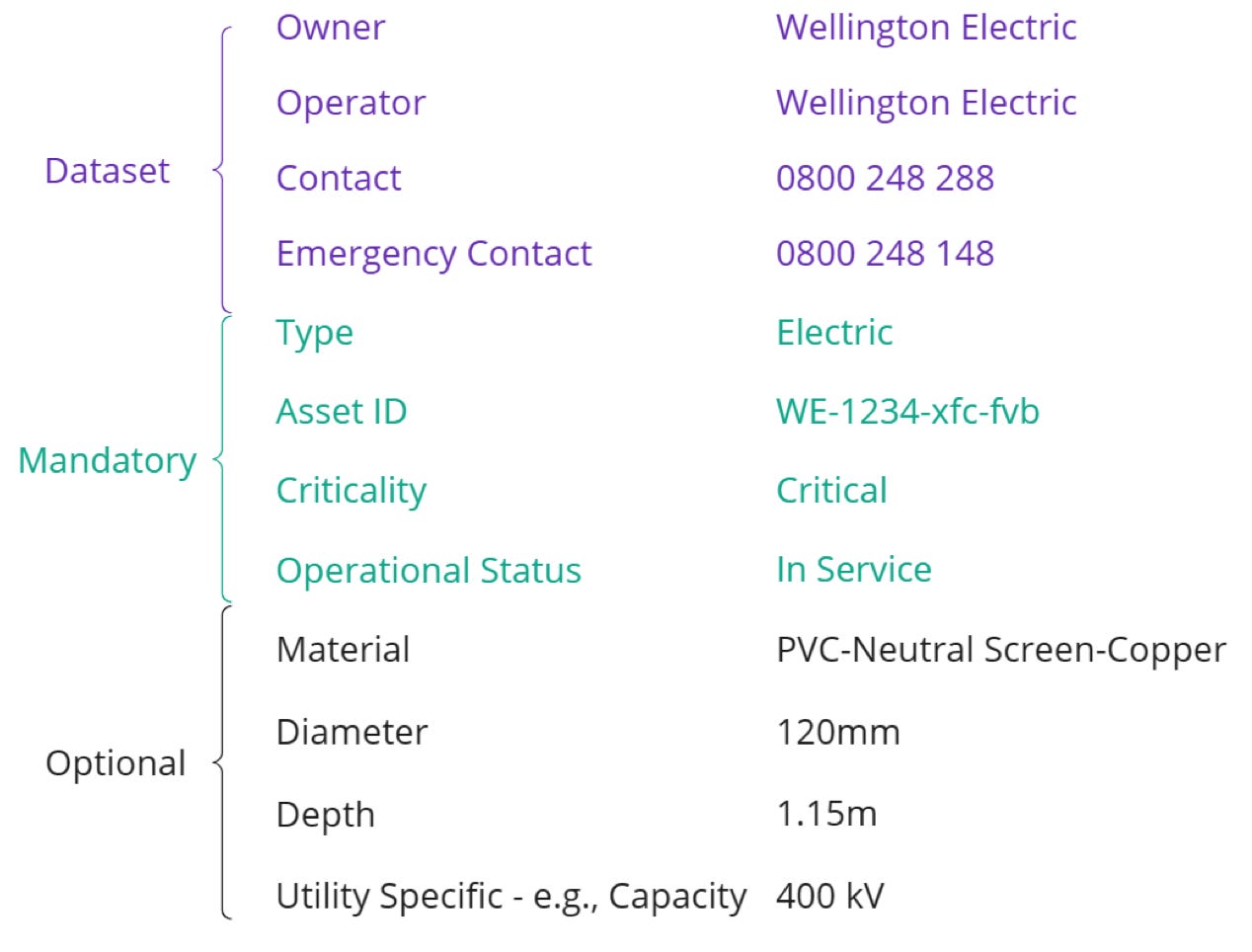

Through this collaboration process - one of the most interesting aspects of the UAR’s experience - partners agreed on the type of information, standards and sharing mechanisms of the UAR. For example, assets’ attributes such as type (water main, sewer, power cable…), ownership, dimension, material, installation data and positional accuracy need to be included in the register. Metadata also describes how each dataset was collected, its refresh rate and usage constraints. See an example of some of the data collected per asset:

The quality of the data is determined based on whether it was derived from existing records or precisely surveyed. Asset owners share it with the platform through APIs or file uploads. Field crews of asset owners or construction companies can also share data directly via a mobile app when they find something while digging. This new information is then sent to the relevant asset owner, who can verify the new information to close the feedback loop.

A last, but critical, piece of the puzzle revolves around the use of this data. Who can access - and how - all this data collected and pooled by the UAR?

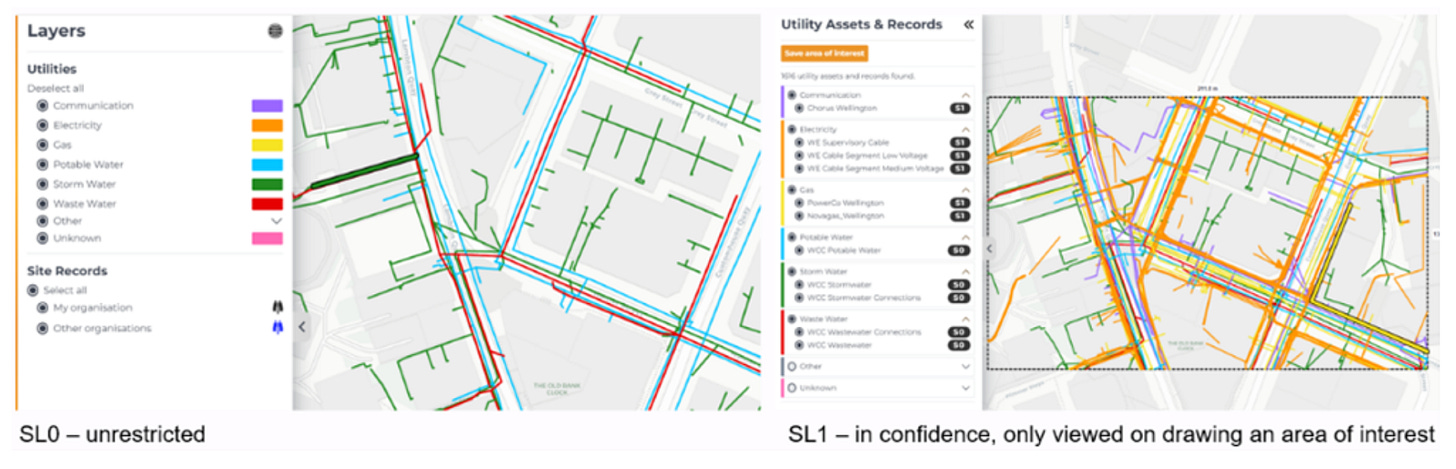

The asset map is offered as a public good, available 24/7, but it is not open access. To visualize it, users from construction and infrastructure companies need to be authorized upon registration. This process demands accepting the terms of use established by UAR. These include, among other, limitations on how data can be used, extracted, and copied from the platform. There are also restrictions depending on the nature of the asset: while some data is directly visible in the Layers menu, other datasets are deemed Security Level 1 and therefore only visualized with authorization.

In essence, different access modalities, from widely available to asset-specific restrictions, enable a wide range of uses while protecting the sensitivity of the data. This shows that, when parties agree and cooperate, it’s possible to overcome the legal and technical hurdles of sharing data and create a system that unlocks its value for different users and different purposes.

This collaboration cannot be taken for granted though. Throughout this process, developed over ten months with research-backed learnings from the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative’s cross-boundary collaboration track, the City Council has engaged with multiple partners, communicating regularly through a newsletter, and participating in many engagement activities. Anyone interested in launching a similarly complex data collaborative project - around underground infrastructure or otherwise - would do well in reviewing the many materials available about the UAR. And this presentation to the City Council is a particularly interesting one - specially for those working in city government.

The lessons from Wellington’s UAR have now scaled to a national level. The NZ Infrastructure Commission has recognised the issue that the New Zealand Underground Asset Register seeks to address as a problem of national importance – and it is now included in their Infrastructure Priorities Programme for further investigation.

Abundance requires sharing

The Abundance agenda has repeatedly highlighted the need to remove barriers to building better and faster for the benefit of communities. Most of the debate centers around the need to remove regulatory barriers - but other aspects, like enhancing data collection and sharing, are as important.

The UAR is a good example of this: mapping underground assets can increase safety for crews, increase the chance of projects running on time and budget, and reduce disruption for businesses and residents.

The benefits are obvious. The legal and tech barriers can also be overcome. The toughest part is aligning everyone with a stake - a cable or a pipe - so they are comfortable sharing the data. There is an art and a science of collaboration, as my colleagues at the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative have documented in detail.2 One implication of this research for the data debate - or any other complex governance challenge really - is that success lies in people. People who can articulate the value, design the system, and convince other people to join in.

That’s the secret truth buried in our cities that the UAR has brought to light.

[Disclosure: I am a Senior Associate and conduct research for the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative, though I was not involved in Wellington’s work. I discovered the UAR through interactions with colleagues but this piece was written using publicly available information. Anyone interested in knowing more can reach out to UAR’s program director, Denise Beazley at Denise.Beazley@wcc.govt.nz]

Currently, a one-off Underground Asset Register fee of $147+GST is charged when an applicant applies for a request for excavation work to help recover the costs of running the register.

See, for example, the list of Stanford Social Innovation Review articles co-authored by Jorrit de Jong, director of the Bloomberg Center for Cities and a leading expert on collaborative governance.