The night before the power outage, I had dinner with some friends: a university professor, a judge, and a manager at a big tech company. No, I’m not about to tell a joke. Half of the time we caught-up, the rest of the dinner we talked about the topic on everyone’s minds - and pockets: housing.

A few days before, we had hosted a group of friends at home to hear Jorge Galindo speak about housing in Spain. Among the many people writing about this in Spain right now, Jorge is trying to push for a very specific and concrete approach: move beyond policies to manage the current stock and focus on substantially increasing housing supply.

This idea is getting traction in policy circles and the public debate more broadly. El Pais dedicated its Saturday editorial to defend speedier housing construction. The day before Jorge’s talk, the Spanish PM announced a plan for industrialized housing construction, as part of a larger set of measures announced in January to increase access to affordable housing.

In other words, it looks like the abundance movement is slowly making its way in Spain. I think this is good news.

The Bank of Spain estimated the need for new housing in 600,000, which will not be met with the current pace of approximately 100,000 new houses built per year. Given the general gap between supply and demand, we need to dramatically increase the number of homes, especially in high-demand places. It seems pure common sense: if housing prices are too high, build more houses!

But, as we discussed at length last Friday, there’s a question that might complicate the story and that I think is worth considering by anyone promoting an abundance approach:

What if something that happens with roads — "induced demand" — also happens with housing?

What if in certain cities, and in particular in certain neighborhoods in those cities, building more homes doesn’t immediately make living there cheaper, because more supply itself attracts even more people who want in?

The Trap of Success

Dynamic cities are magnets. They produce jobs, culture, financial and social capital — the stuff that powers entire economies. But that success often comes with a cost: unaffordable housing prices. And when housing gets too expensive, innovation slows. As Pieter Garicano put it, housing policy is innovation policy. It’s also social policy, but let’s focus on the innovation side for now.

The answer to the housing crisis seems obvious: build more houses. Clearly, in many cities, there is a massive gap between the number of people who want to live there and the number of homes available.

Jorge uses the metaphor of a queue to describe the issue. Right now the line to access the “Houses and Co.” store is way too long, and only certain people in the front slots will get in. We need to make the shop much bigger. The question is, how big? And what if, for particular housing stores, for certain urban markets, the potential line is way too long?

Maybe it's even endless. You may double the size of the shop, but then, suddenly, way more people will show up, because now it's easier to get in. And the line? Still just as long.

Some cities - and some neighborhoods in certain cities - are like that store. There’s a huge pool of people who would move to Latina, Centro or Salamanca in Madrid, if only they could. Students, remote workers, rich foreign retirees… all waiting in the wings. The moment you build new units, latent demand, that is, demand that was hidden or suppressed, rushes in to fill the gap.

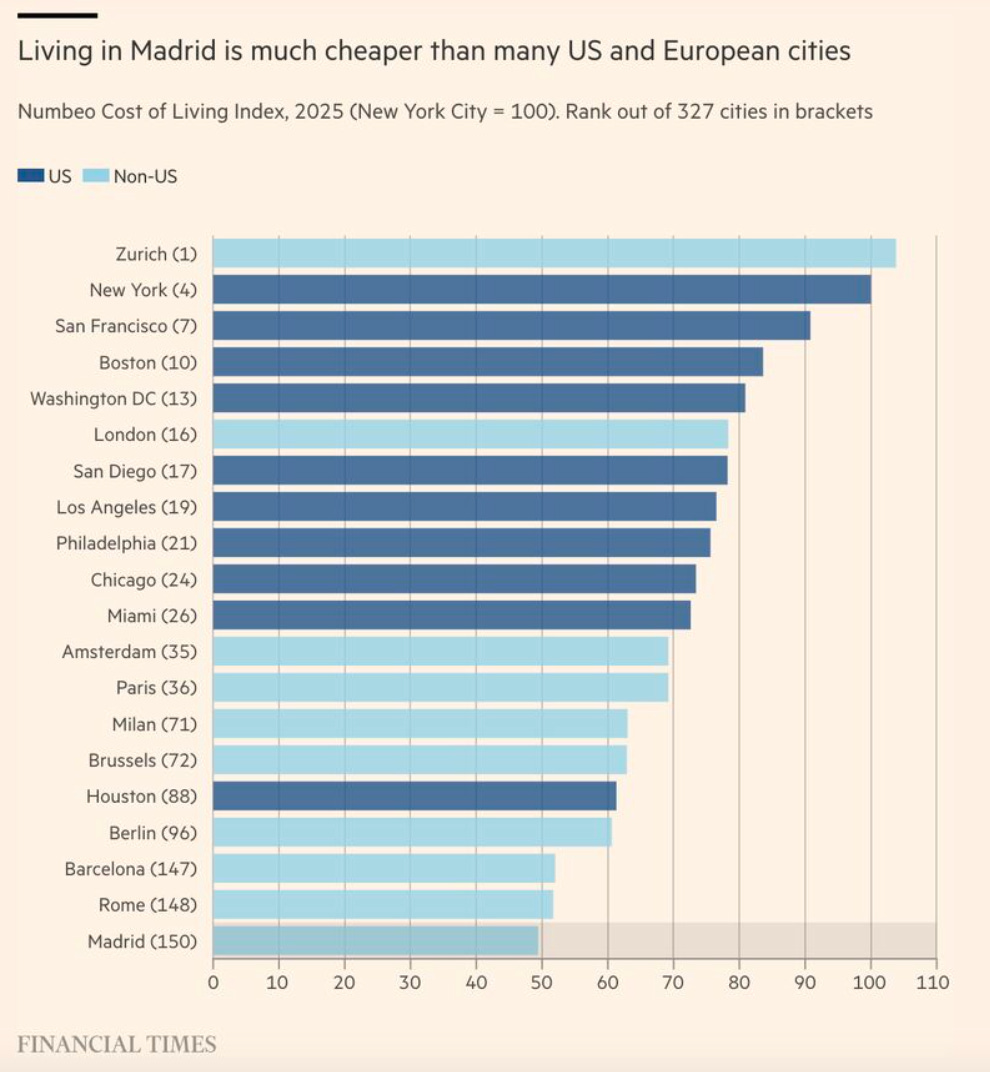

In these places, demand isn't just high; it's potentially unlimited. Even more so if the city is cheaper for potential buyers from abroad. For every apartment you build in the trendy Madrid neighborhood of Justicia, ten more people realize they'd love to live there too.

The result: prices stay high, or even rise, despite new supply.1

This doesn’t mean supply doesn’t matter. It means that supply and demand are dancing partners, and when you move one, the other moves too.

So, What Do We Do?

The demand may be endless, but the solutions to this paradox are limited. We discussed at least two late-night on Friday:

Go All In: Build Up and at Scale

You could build so much new housing — and so quickly — that even the endless latent demand can’t keep up. Build wide, and build up, without height restrictions, like the massive towers of Tokyo.

The first thousand units might get absorbed immediately. The second thousand too. But eventually, after building tens or hundreds of thousands of units, supply will engulf the deep pool of latent demand. Prices would have no choice but to level out.

Even if there were no restrictions or limitations to building out and up - a big “if” - this approach has a problem. The same features that make a city attractive may be destroyed in the process. Status matters. Aesthetics matter. By transforming the shop into a mall, you may annihilate its soul, the thing that makes it interesting in the first place.

For some, this may not be bad per se. As long as the city preserves its magnetic power through a deep labor market and service offering while keeping negative externalities at bay, we should make housing markets as liquid and as responsive to demand as possible.

Yet again, supply and demand dance together, and transforming a jazz club into a massive music festival changes the dance altogether.

Create New Centers: The Fractal City

The other strategy is more elegant: create a larger number of attractive neighborhoods. Imagine a city as a fractal, with many centers, each vibrant in its own right. Give people reasons to live, work, and thrive in new hubs — with good transit, good public spaces, good services.

By distributing desirability, you reduce the pressure cooker effect on the original prime locations. It’s a slower process than bulldozing or building up. But it’s often more politically, environmentally, and socially sustainable.

As tasteful as it sounds, this approach also has some challenges, but I will leave that discussion for future posts where I want to delve deep into the work by Ramon Gras at Aretian Urban Analytics and others.

Better to be Dynamic than Manage Decay

We shouldn't be naïve: building new housing won’t instantly "solve" affordability everywhere.2 But refusing to build guarantees stagnation, exclusivity, and slow decay.

Even if prices don't collapse, more housing is still better than no or little housing. A city that welcomes more people is healthier than a city that gates itself off. Newcomers bring energy, ideas, and diversity. A city that stays alive stays dynamic, even if affordability remains a challenge.

This also means that just building more houses will not be enough. Increasing supply in high-demand locations will increase dynamism, but will need to be complemented by additional, environmentally sustainable, housing in other places and the creation of distributed economic activity. This, in turn, means investing in mobility options - time travelled to work is also a cost - and other services. Looking at housing as a social policy, and not just an innovation policy, demands other tools, and I will write about those at another time.

The main argument, however, stands. Rather than manage the existing stock of housing, transport, and amenities, what we need are policies that promote a bounty of goods and services, particularly those with higher social value. Rather than worrying about induced demand, let’s try to bring as many people in as possible. As I told Jorge when he asked me whether he could invite a few people to his talk at our home, we only have one strict “zoning” rule: The More, The Merrier.

Here the mechanism is a bit different than induced demand in traffic. In mobility, demand can rapidly increase because it’s highly elastic, it’s easy to go back to using the car if they build another road. Deciding to move to a city because they have built new housing is not that easy. The “induced” demand here derives not so much from the elasticity of the demand, but due to the potentially massive latent demand to live in particular locations.

According to the “Filtering theory” new supply of high-end housing units will eventually trickle down to other housing units too. See, for example: Mense, Andreas (2025). "The Impact of New Housing Supply on the Distribution of Rents". Journal of Political Economy Macroeconomics. 3 (1): 1–42. See also Been, Vicki and co-authors (2018) “Supply Skepticism: Housing Supply and Affordability” from the Furman Center at NYU for a summary of the arguments against induced demand in housing and defending the filtering theory. I am not 100% convinced that these arguments will hold in every urban housing market.

Muy buen artículo!

Hace poco escribí un post sobre este tema. Lo podéis ver en mi perfil.

Dentro de poco haré uno analizando el porqué de este problema.